Grey Hours: A Psychologist and Survivor’s Journey Through Depression

By Scherezade Siobhan

A decade ago, when I was swept by a giant wave of major depressive disorder (MDD), I would step out of my room every morning with a well-rehearsed nonchalance, a permanent scowl to insert suitable distance between myself and anyone else who would ask me how I was doing, and mostly unironed clothes. I had learned to disguise my predicament, learned to layer it up in bolts of dead air and a spurious poise.

It was expected out of me — to not be ill, to not be in possession of mind slowly coming to terms with its chasms. I would drag the red impulse of self-injury through the length of every meeting, every conversation, every subway-stop. It was almost as if I had stopped existing as myself and was carrying my physical body as a straw effigy slowly being doused with kerosene. Any moment, I expected the dawn of an impregnable explosion. I spent days, weeks, months living in this unmitigated hell. No one knew. No one was allowed to know. I wasn’t allowed to tell.

When I say allowed, it isn’t as if there were visible, forced compulsions levied on me to not express the pain I was in. There was no regulator outside of my own self who forbade me from telling my best friend that I could not attend her engagement because I was incapable of switching on the light in my own room, let alone get dressed in my gaudiest lehenga and dance till my limbs were sore, as much as I had wanted to. So, I told her I had severe viral fever and wished her the most blessed marital journey.

I suppose I suffered from many consecutive episodes of “viral fever” during this time. My former boss recommended a series of ayurvedic treatments to boost my immunity, an Auntyjee in my building gave me the visiting card of an Ashtanga yoga center, another friend sent me a care package that contained 12 vials of flower remedies for “body purification”. I politely thanked each temporary sympathiser knowing fully well that the very same people would be at complete loss of understanding if I actually did tell them what my “real” illness was.

I had done this so many times, I had it down to a routine. I could augur the triggers, the first faint appearance of nameless anxieties followed by a full-fledged immersion into grief. In my experience as a psychologist and also a survivor of major depressive disorder, most people assume depression is a function of sadness; if you can just cheer up and act happy, you will feel happy.

UNDERSTANDING DEPRESSION: SADNESS VS GRIEF

This is the biggest gap in comprehension between those of us who are neurodivergent and those who aren’t — the linearity of such a definition betrays its comorbidity. There is a pronounced difference between sadness and grief. Sadness is transient, usually rooted in some perceivable event or incident; grief is multi-pronged, runs in every direction and the locus of trauma is usually invisible or imperceptible.

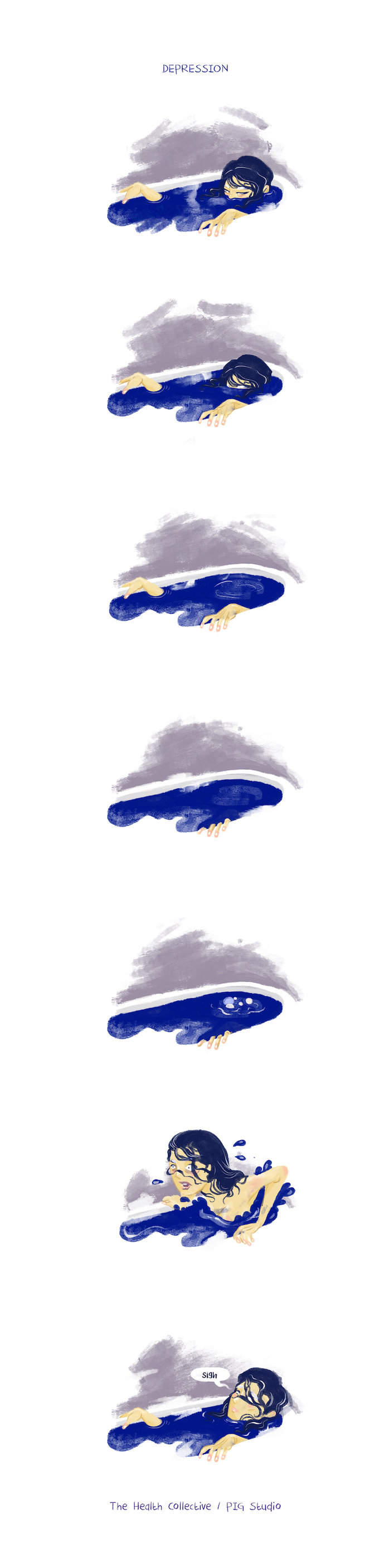

Yes, I do experience sadness time to time but it is very different from the titanic surges of grief that pummel me hollow every time a depressive cycle sets in. Fact is: it is not necessary for depression to arrive with sadness or a sad event, sometimes my depression knuckles itself out from underneath my therapy-fed composure right in the middle of a celebration or an achievement. I have interred myself into its foxhole right after I signed my first book contract or when I did really well on my dissertation defence. It is a poly-limbed hydra that suddenly grows into a colossus shadowing everything else in your life. I once watched a movie where as a form of ancient punishment, a queen was blindfolded, had her ankles and hands tied with iron chains and was pushed into the deep blue mouth of a calm sea. This is the closest representation of depression I can think of. You are spent slowly but continuously. Your exhaustion is so intemperate, you reach a space where survival isn’t about feeling better, it is merely about feeling lesser than this.

ALSO READ: Overcoming Depression: A Non-Stop Fight

The stigma around mental health is still fairly verbose and athletic. It never runs out of breath decrying neurodiversity as hokum or sufferers of psychiatric misdiagnosis as people who are merely in need of attention.

A common approach to talking about mental health and illness is to constantly highlight it as an individual’s choice and challenge. The unhealthy cynosure is always a brand of generic advice that somehow hinges squarely on deciding that a person alone is expected to “fix” their mental health issues. This is a reductionist and patchy narrative. Mental health is a composite of neurophysiological aspects as well as socio-economic, cultural and ecological factors that determine the diameter of its field of reference. If we exclude any component of this elaborate blueprint, we are willfully failing to recognise the dimensions of its true shape.

There is a constantly instructional approach to how people outside the depression spectrum —particularly those who are a part of traditionalist mental health practice — engage with those who experience depression. It borders on infantilising the comprehension faculties of those who are dealing with this illness (or condition, dependent on how folks want to claim agency) on a daily basis. This didactic manner is alienating and severely lacking in even attempting to establish constitutive insights.

A significant number of my clients are aware that physical activity and routine-setting is useful as well as highly recommended — the schism usually lies between this awareness and its actualisation. I often remember Sarah Kane’s prescient declaration in 4.48 Psychosis: “I know. I’m angry because I understand, not because I don’t.” It is a fallacy to assume that someone who has been handling, hell even battling, depression for a while doesn’t understand that the sweeping bustle of interpersonal engagement might alleviate some of the lows but the fact is, they are not capable in the moment to engage with anyone or anything. The self-care culture was initiated as a movement for promoting self-worth, evaluating the scope of continuous emotional labour and directing compassionate energy towards one’s own self first. Lately, though, it has transformed into a consumerist exercise in selling unpronounceable herbal teas and branded yoga pants. I am not knocking down the fact that we all need to create our own mini mind-altars of care, indulgence and sheer ardency for our respective survival but it would be an error to give unnecessary currency to the fetishisation of individual wellness as separate from community-oriented modes.

There are two common myths about depression that need immediate debunking –

- Depression is a state of sadness – Depression is a condition that debilitates the moods spectrum. The term itself is widely misused to generalise a host of different, maladapted cognitive, emotional, physical and behavioural patterns that impact the way our moods hold sway over our perception of reality. We often misinterpret the word mood in its core meaning as well – it isn’t a whimsical shuffle of feelings; it is a labyrinth of emotional states which means it is more ambiguous and less predictable in most cases. On the one hand, depressive symptoms could be a more chronic, veiled yet prolonged and those are categorised under dysthymia or persistent depressive disorder (PDD), on the other it could be more periodic, deeply seismic and a severe spiral occurs into seemingly hopeless lows structuring their own clockwork patterns of sorts; this is more likely to be emblematic of clinical depression or a major depressive disorder (MDD).Reaching out and getting clinical help should be the foremost step for anyone who is going through these states on a continuous basis. Lots of times, depressive moods co-occur with other mental or personality based conditions including a borderline personality or trauma. This is called comorbidity in clinical psychology. The presence of these variants cancels out any puerile assumptions about someone “choosing” out of their “sadness”. Depression is usually an inability to access a host of emotions. (I always thought of my own depression as anger with its tongue cut out. An inevitability I couldn’t fathom.) Therefore, one of the best ways to work with one’s depressive states is to find a way rewiring our distorted self-perception that makes us devalue ourselves and imagine a grey endlessness of lack in ourselves. Combining medication with evidence-based therapeutic approaches such as biofeedback, cognitive behavioural therapy, somatic therapy among others have repeatedly shown improvement in not just basic functionality but a resurgence of desire to participate life by one’s own will.

- Depression is only an individual’s illness – In Mark Fisher’s ingenious essay “Good for Nothing”, a stand out line is “Individuals will blame themselves rather than social structures, which in any case they have been induced into believing do not really exist (they are just excuses, called upon by the weak).” Fisher describes this idea of responsiblisation – a hierarchical subjugation that makes those disconnected from inherited privilege and power feel that they alone are responsible for their oppression – in depth, as he asks us to reconsider how we analyse and parse our interpretations of mental illness as well as wellness in this world. Depression cannot be decontextualised from the social, political, economic and cultural orders that enable its existence. Yes, it is a unique experience for each person who is trying to cope and survive but we must also look at it under the lens of collective causation as well as effects. It is safe to say that going for a walk is a great idea but as a woman living in India, my first thought is usually directed towards how safe it would be to do so, particularly late at night when I usually find the time to go for a walk. We can’t disregard social structures that serve to keep the idea of “madness” profitable. In India, classism, casteism, racialisation, misogyny are all key contributing factors to mental health. If we truly want to measure the tidal impact of tsunamis, it is deeply ignorant to try and ignore the rest of the ocean and only focus on individual waves.

If we honestly want to address the global epidemic of depression spectrum illnesses, we have to recognise that instead of repeatedly placing the burden of “reaching out” on the shoulders of survivors, perhaps we need a “reach in” movement for the rest of the people around them. Maybe we need to recognise that asking for help is hard because culturally we are taught to baulk at the idea of vulnerability as an offshoot of weakness. Maybe we need to start by accepting that we need to move beyond conversations about tolerance and acceptance for mental health and illness, focusing instead how to centre the dialogue for care on the needs and requirements of those dealing with these conditions. We have to start talking to and talking with not talking down to survivors of mental illness.

Scherezade Siobhan is an award-winning Indo-Rroma Jungian scarab turned psychologist, mental health advocate, community catalyst, and a writer. She is the founder of The Talking Compass — a therapeutic practice that provides in-person, at-home and online counselling for people who need help with emotional and mental health. She is the creator and curator of The Mira Project, a global dialogue on women’s mental health, gendered violence, and street harassment. Send her puppies and cupcakes at nihilistwaffles@gmail.com

Disclaimer: Views expressed are personal. Material on The Health Collective cannot substitute for expert advice from a trained professional.

If you would like to share your story, do write to us here or tweet us @healthcollectif

Feature Image: Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

Pingback: Your Stories: Battling Stigma, Expectations and other Burdens as a Young Adult with Depression

I am lucky that I found this website, precisely the right information that I was searching

for!